Authored by Cello Health, now part of Lumanity

As we adapt to living and doing business in the evolving environment caused by COVID-19, we should seriously reflect on the enormous disruption the pandemic has had on clinical development. For the many hundreds of thousands of people participating in trials every year, and those relying on the new treatments being studied, the delays and upheaval have caused exceptional distress and worry, especially for those relying on breakthrough therapies in areas of the greatest unmet need.

There is now more welcome news provided by recent reports that many trials are on the rebound and once again enrolling and progressing, and also that the lessons learned from the intense research activity to rapidly develop vaccines and treatments for COVID-19 can be more broadly applied in the future to accelerate subsequent clinical trials. However, there is also the recognition that many of the clinical trial and regulatory flexibilities that are being granted at this time are in response to the unprecedented public health challenge, and should not necessarily all be viewed as part of the ‘new normal’ of clinical development.

To add flavor to these assertions, let’s look in more detail at:

- The magnitude of the impact COVID-19 clinical development in terms of trial activity, across geographies and therapeutic areas – and how this is recovering

- How clinical trials were accelerated in the age of coronavirus, with the UK RECOVERY trial as an example

- Will learnings and approaches from our response to the coronavirus outbreak make it quicker and easier to trial drugs in the future?

- After-effects of COVID-19 on clinical development

What is the magnitude of the impact COVID-19 on clinical trials?

Monitoring current clinical trials and comparing activity with the same time last year helps us to understand and grasp the magnitude of the impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials in terms of trial activity, across geographies and therapeutic areas.

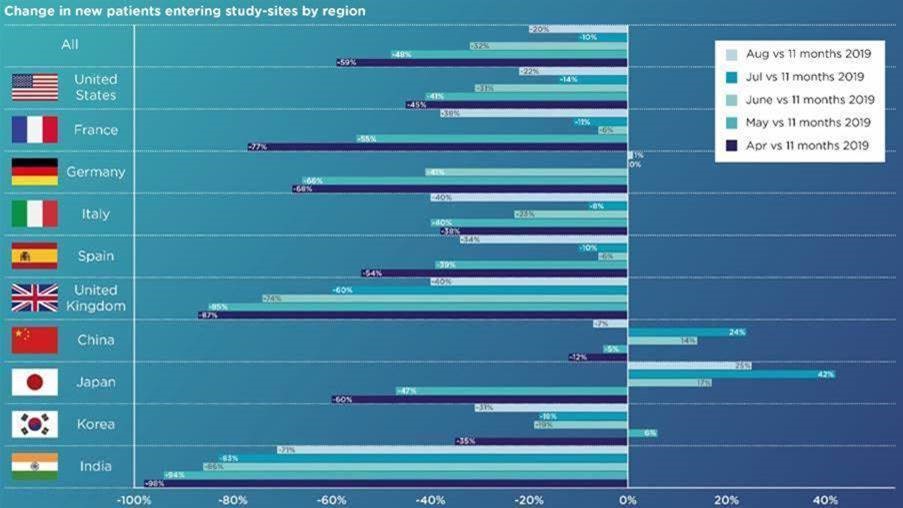

The graph below is from the most recent Medidata report1 and shows enormous and alarming changes in new patients entering clinical trials, by region, versus 2019. Anywhere between a 45%–98% reduction in enrolment was seen in April. It was noted that the negative effects of COVID-19 on new patients entering study-sites are likely understated, as we are looking at trials that are still actively recruiting patients.

Recovery continues to vary greatly by geographic region due to the varying impact of the disease, and policies and responses adapted over time.

To be parochial for a moment, the UK saw some improvement, moving from -87% in April to -60% in July to -40% in August compared to its pre-COVID baseline.

In the US, the impact was seemingly less, with only a 45% drop in recruitment in April. A steady improvement was seen over the summer until August when it worsened to -22% from -14% in July. Strangely, this is against a background of a decrease in the COVID-19 case rate as compared to July.

A similar pattern and drop in recruitment in August is mirrored in many European countries such as France, Italy and Spain and, in these countries, it does reflect a sharp spike in COVID-19 cases.

In Asia, there has also been a reversal of the improvement in recruitment previously witnessed in July for China and Japan. Korea also has seen a dip in new patient flow in August. The exception is India, which is continuing a slow recovery.

Dramatically, in July, the Scottish Parliament’s cross-party group on cancer revealed a 95% reduction in patients entering oncology clinical trials.2 They also highlighted the risk of long-term impact as a result of the closure of swathes of the health service in anticipation of treating the pandemic, and there has been a “profound impact” on early cancer diagnosis, a fall in urgent referrals from GPs, reduced service capacity and a cancellation of screening programs. This is a startling figure, and not reflective of the pattern observed globally.

The Medidata reported a global downturn in recruitment to oncology trials of -41% at the start of the pandemic, which highlights the severity of the situation in Scotland. For context, all therapy areas experienced an alarming drop in recruitment at the start of the pandemic; endocrine -82%, cardiovascular -97%, CNS -65%. Overall Oncology and Cardiovascular have rebounded most successfully since April, standing at -6% and -20% of the 2019 activity respectively. In contrast, enrolment in CNS, dermatology, endocrine and respiratory trials is still down by a mean of 40%.

How clinical trials were accelerated in the age of coronavirus – The UK RECOVERY trial

Writing for Nature, Nicole Mather, an executive board member at NHS DigiTrials, explained how the RECOVERY trial was conducted so rapidly, and how this may be broadly applied in the future to accelerate subsequent clinical trials. She said: “The RECOVERY trial had five key features which distinguished it from a standard approach.”3

The first of these features is a flexible protocol which lays out the study’s design, data and regulatory requirements in just 20 short pages. The second is the rapid granting of ethical and regulatory approval. Usually, this process can take 30–60 days; the RECOVERY trial did it in nine. The third is the simple recruitment procedure, requiring patients to fill out a consent form of just two pages, and clinicians filling out a one-page bedside form. Fourthly, the RECOVERY trial utilized the NHS DigiTrial services (set up in 2019 for planning large clinical trials) to collect and process data rapidly. Finally, the results of these analyses were quickly made public, being published within a month.

COVID-19: A catalyst for change?

What are the positives to come out of the pandemic? Will learnings and approaches from our response to the coronavirus outbreak make it quicker and easier to trial drugs in the future?

The initial responses of many sites to the pandemic have necessarily been negative, with 15% cancelling trials, 30% delaying the start of new trials and > 40% halting recruitment to ongoing trials. However, there have also been some extremely positive and innovative reactions in terms of protocol amendments, flexibility in patient engagement and switching to virtual trials, which have been achieved in a minimum of 40% of sites.1

Patient advocates have long pushed for more virtual trials, which ease the burden of clinical trial participation. If the trend catches on, it could speed up the identification, recruitment and retention of participants – a significant element of the drug-development timeline and a key focus of our work.

The pandemic exponentially accelerated the adoption curve of virtual trials and forced the FDA to finally release guidelines. The impact of COVID-19 could catalyse lasting change in other ways, including the increased culture of collaboration across government, industry and academia that has emerged during the outbreak and also Pharmaceutical companies might make long-lasting adjustments to their supply chains.

As stated by Nicole Mather, NHS DigiTrials lead on the UK RECOVERY trial, “It seems clear that a more straightforward and pared-down approach to clinical trials can greatly accelerate the rate of completion and treatment discovery, without sacrificing peer review or bypassing regulatory processes. Now all that remains to do is to apply the lessons learned from the successes of RECOVERY to future clinical trials”.3

This is definitely the goal, however, the industry, regulators, academia, health services and patients must not lose sight of the fact that it has been the unique public health challenge posed by the pandemic that has driven the flex in many of the regulatory and clinical approaches, and these are not necessarily appropriate or sustainable as part of the ‘new normal’ of clinical development.

One would hope that some pragmatism will continue in key topics such as triggers for protocol amendments and deviation processes; risk assessment expectations; continuing or stopping trials; continued subject participation; informed consent (including e-Consent) and remote monitoring.

After-effects of COVID-19

As all stakeholders adapt to the short-term challenges of the pandemic, we should all look at the longer-term implications for clinical development, patients and the industry. There will undoubtedly be a major price to pay by patients and carers, particularly those waiting for breakthrough therapies in areas of the greatest unmet need. We can anticipate potentially severe cash flow issues for drug developers. Small to medium-sized Pharma and Biotechs may be most vulnerable, particularly companies with a single asset. There is also potentially an impact on a policy level, including in drug pricing negotiations.

What can we do now to help minimise the after-effects? One critical need is to dramatically accelerate patient enrolment in all trials to try and make up for lost time. We can all play a part in this.

A commitment to approaching such questions rigorously and by sustaining a focus on virtual clinical trial networks and maintaining the balance between patient safety and trial integrity and the pressures of funding and revenue considerations will improve the care we can provide to all patients – in the COVID-19 era and beyond.

“…in July, the Scottish Parliament’s cross-party group on cancer revealed a 95% reduction in patients entering oncology clinical trials”2

References

- Medidata. COVID-19 and Clinical Trials: The Medidata Perspective. Release 9.0. https://www.medidata.com/en/insight/covid-19-and-clinical-trials-the-medidata-perspective/ Accessed 4 October 2020.

- Malik, P. NHS Scotland recovery group launches as cross-party group shows 95% drop in cancer clinical trials. The Press and Journal. https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/news/politics/scottish-politics/2294420/nhs-scotland-recovery-group-launches-as-cross-party-group-shows-95-drop-in-cancer-clinical-trials/ Accessed 4 October 2020.

- Mather, N. How we accelerated clinical trials in the age of coronavirus. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02416-z Accessed 4 October 2020.