Introduction

The generic drug market in the United States is critical to the financial sustainability of the healthcare system, providing lower cost alternatives to brand-name medications and contributing to significant savings for both patients and the healthcare system. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)1 of 2022 introduces several provisions aimed at reducing drug prices in Medicare for selected drugs to reduce out of pocket costs for some beneficiaries. While the full consequences of the IRA are not yet realized, these provisions have the potential to undermine the financial sustainability of the generic drug industry.

Historical Perspective

Congress enacted the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, in 1984 to balance incentives for innovation while fostering a robust generic drug market. The established framework did this in part by creating a streamlined process for generic drug approvals. Prior to passage of Hatch-Waxman, just 19%2 of prescriptions in the U.S. were filled with generics and only 35%2 of top-selling pharmaceuticals had generic competitors after their patents expired. Moreover, it took 3 to 5 years for generics to enter the market after the patents on brand-name pharmaceuticals expired.

Current Generic U.S. Landscape

Today, generics account for approximately 90%3 of all prescriptions dispensed, although they represent a lower percentage (12%)4 of total drug spending due to their lower prices. Moreover, the average effective patent life for small molecule drugs before generics enter the market today is 13 to 14 years5—demonstrating this balanced framework has proven successful in encouraging introduction of innovative drugs while ensuring swift market entry of generics. This success is also reflected in the savings generics drive in the health care system. The Food and Drug Administration estimates that new generic drugs approved in 2018, 2019, and 2020 resulted in approximately $53.3 billion in savings in each of those years.6 But importantly, these savings accumulate over time as more generics are approved providing long term value to the healthcare system while new brand drugs continue to enter the market. Overall, generics are a crucial tool in controlling costs and increasing access to drugs.

Generic drug manufacturers are experiencing increasing demand but also increasing pricing pressure from continued consolidation of buyers (e.g., wholesale buying consortia, pharmacy benefit managers and group purchasing organizations) that gain leverage to lower prices. They also face increasing competition from new companies within the U.S. and abroad, further decreasing prices. Most alarmingly, as prices fall over time with increased competition, manufacturers are deciding to stop the manufacture of generics, particularly sterile injectables7, as they have become unprofitable. This can lead to insufficient market supply and drug shortages, ultimately impacting the patients who need them the most.8

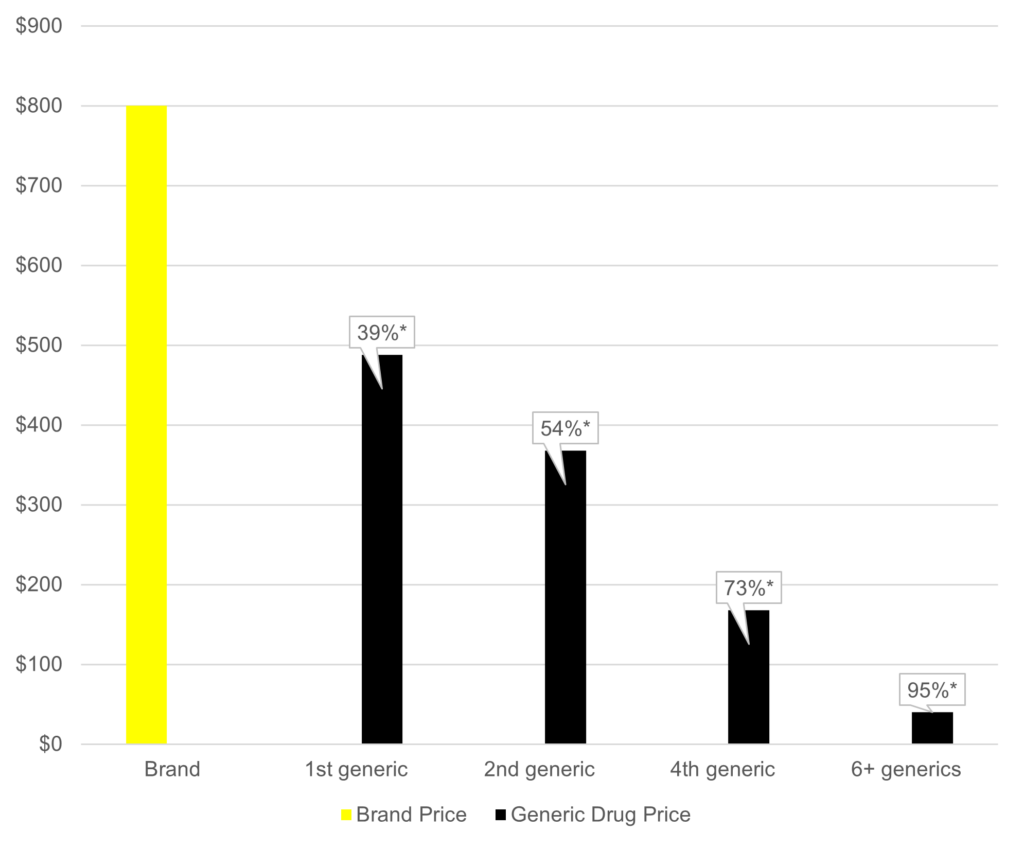

Generic manufacturers consider various factors prior to entering the market including market need, timing of regulatory submissions to ensure alignment with brand drug patent expirations, and the size of the financial opportunity (i.e., projected drug price and market share). Being the first generic to market under Hatch-Waxman can provide the opportunity for a 180-day period of exclusivity9 during which time there is limited or no competition from other generics. In this way, the framework encourages generics to enter the market swiftly in order to capture market share before additional generic competitors reach the market. When a single generic is on the market, the generic average manufacturer price (AMP) falls by 39%. When two generics are on the market, the generic AMP falls by 54%. Generic prices continue to fall as the number of generic products on the market increase. When six or more generics enter the market, the generic AMP falls by a staggering 95% for most drugs (Figure 1).10

Figure 1. Impact of Generic Entry on Drug Prices10

*Percent reduction in average manufacturer price (AMP)

Impact of the IRA on Generic Manufacturers

The provisions of the IRA most impactful to the drug industry are those seeking to lower costs for prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries and the government. One of the main components of the IRA related to these objectives is establishing theMedicare Drug Price Negotiation Program under which CMS is authorized to determine maximum fair prices (MFPs) for certain high-gross-expenditure, single-source drugs, and biological products covered by Medicare.11 The process targets drugs without an approved and marketed generic or licensed and marketed biosimilar competitor at the time of selection. In guidance CMS added a requirement that the competitor also be “bona fide” marketed.

Generic manufacturers are attracted to branded drugs with high-volume sales and larger financial opportunity prior to patent expiration where there is a stronger likelihood of achieving significant market share.12 Unfortunately, it is precisely these branded drugs that are targeted by the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. The unintended consequence may be a significant disruption to these historic dynamics, creating a new – and less beneficial – paradigm for generic manufacturers.

Lower brand drug prices reduce incentives for generic entry

Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, MFPs for brand medications are likely to reduce incentives for generic manufacturers to enter the market with a generic version of the medication that must compete with the MFP. Reduced price differentials can lead to lower revenue for generic manufacturers, potentially deterring investment in manufacturing generic products. If fewer generic products enter the market, there will be less competition, and the full cost savings potential of generics may not be realized.

Reduced investment in small molecules ultimately means fewer generics

CMS’ Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program reduces incentives for brand manufacturers to invest in small molecules due to the shorter timeline to MFP compared to biologics. Small molecule drugs can be selected 7 years post FDA approval, whereas biologics are afforded a longer runway after approval (11 years) before becoming eligible for selection. To navigate price pressures, brand manufacturers may shift research and development (R&D) to developing biologic drugs for complex conditions with higher price points, offering a longer time to achieve returns on investment. Pharmaceutical manufacturers have been shifting development away from small molecules toward biologics for quite some time, and this trend may intensify under the IRA.13

There are reasons to be concerned about a reduction in small molecule drug development. Small molecule medicines provide critical clinical benefits that cannot be replicated by biological medicines, such as the ability to reach therapeutic targets inside cells and cross the blood-brain barrier. They also provide great flexibility and convenience for patients as most can be easily self-administered, reducing barriers to treatment adherence.

From the perspective of the generics industry, however, fewer new small molecule drugs ultimately means fewer opportunities to develop generic versions of those drugs. For the healthcare system, it means fewer drugs traveling the well-established and highly efficient regulatory pathway to genericization, and the cost savings associated with it.

Greater competition among generic manufacturers may also lead to further consolidation within the industry. Ultimately, fewer generic companies chasing fewer generic development opportunities will erode the current cost savings realized from the industry today.

Reduced brand market share from fewer brand indications further reduces generic entry incentives

Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program there may be less incentive for brand manufacturers to invest in additional indications for FDA-approved drugs as CMS will select small molecules that have been on the market for 7 or more years, which is far earlier than the 13-14 years they now average before facing generic competition. This limits the time to earn returns on investment costs for new indications, since the brand price is reduced prior to patent expiration. In reaction to the loss of revenue in the years after the MFP is in effect, brand manufacturers are likely to scale back clinical development programs since patent protections or regulatory exclusivities for new indications will not delay eligibility for selection.14 In disease areas where post-approval indications are common in bringing new treatment options, including cancer, chronic diseases and rare diseases, these impacts are expected to be more acute.

A decrease in new indications will reduce market share of branded products, making it financially more challenging for generic manufacturers to develop and launch new generics.

Market access impacts

Despite the assumption that the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program will lower brand drug prices in Medicare for the drugs that are selected, the IRA as it is currently written does not restrict payers from preferring highly rebated, high list price brands over lower cost brands and generics. In fact, payers have publicly stated they expect brand manufacturers to continue to offer rebates to maintain formulary preference over new to market generics. They may continue to be incentivized to prefer high-cost drugs that offer rebates over lower cost products, further reducing brand net prices.15

As a result, payers may place generics and biosimilars on higher tiers with higher copayments, making them more expensive for patients. Government investigators have noted pharmacy benefit managers and health plans may be incentivized to cover reference brand products that deliver rebates and support payers’ profits over lower cost generics, which may contribute to this dynamic. This may be evident in that currently, when a new generic comes to market, it takes approximately three years before it is covered on over 50% of Medicare Part D plans.3

FTC stated in 2022 and reiterated in 2024 that “rebates and fees may shift costs and misalign incentives in a way that ultimately increases patients’ costs and stifles competition from lower-cost drugs, especially when generics and biosimilars are excluded or disfavored on formularies.”16

Spillover effects broaden the impact

The effect of the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program will not be limited to selected drugs with MFPs but will extend to other drugs and other payer markets. A lower price on the selected drug will incentivize payers to negotiate lower prices for all related products in the same or similar therapeutic class. In addition, it is common for payers to align their commercial and Part D formularies. Payers have indicated that they will use published MFPs as a baseline for negotiations across their commercial business as well as Medicare to offset increased liabilities under Part D redesign.17

All branded drugs in the same class as an MFP drug will have increased pressures in both commercial and Medicare markets. New generics within these therapeutic classes will need to compete with MFPs while incentivizing payers to cover them, which may prove to be an impossible task given the market trends and pressure on generic manufacturers.’ As such, the IRA will have far reaching effects that further erode generic drug development incentives, threatening the promise of competition and lower prices created by the IRA.

Unintended Consequences

The IRA will fundamentally change the nature of the opportunity for new generics. Because the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program targets the most successful branded products, the very products that are most attractive to generic manufacturers, the IRA could impact the extent to which generics remain a critical driver of value to the health care system.

There are several reasons why policymakers should be concerned about the possibility that the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program will negatively impact a thriving competitive generics market. Robust generic markets with multiple manufacturers have benefits for supply chain resiliency, drug plan sustainability, and, most critically, access to medicines.18

First, robust generic markets are vital to ensure a reliable supply of low-cost generics which provide needed treatment options to patients. Generic entry after loss of exclusivity for most branded drugs within a therapeutic class provides patients low-cost access to the therapeutic option that works best for them. In addition, the introduction of government determined MFP’s into an otherwise market-based system will do nothing to curb the incentives that drive health plans to prefer higher-priced drugs that offer large rebates over selected products with MFPs, which can result in reduced patient access to the full range of treatment options within a therapeutic class.

Second, strong generic markets with multiple manufacturers per drug supports a resilient supply chain.18 A robust generic market attracts multiple manufacturers to invest in producing generic versions of a branded drug that loses exclusivity which helps mitigate supply disruptions.19,20 Drugs with an MFP may not have revenue incentives to maintain their robust supply.

In short, strong generic markets have been vital to ensuring a reliable supply of low-cost generics which provide more treatment options to patients and support the stability of healthcare systems through cost savings. The IRA could impact the extent to which generic manufacturers remain a critical driver of value to the health care system.

Key Takeaways

- A vibrant generics market in the United States has generated savings for decades, reducing prices up to 95% for most drugs

- Strong generic markets are vital to ensure a reliable supply of low-cost medicines which provide additional options to patients and support the stability of healthcare systems through cost savings

- The introduction of the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program under the Inflation Reduction Act is expected to undermine the generic drug market in a number of ways:

- The IRA forces generic companies to compete with a government-determined price, reducing incentives for generic market entry.

- By disincentivizing development of new small molecule medicines, and disincentivizing continued development of those medicines after they launch, the IRA reduces the number of branded reference products attractive to generic companies

- The IRA reduces insurer incentives to promote utilization of lower-cost generic drugs

- By targeting some of the highest selling brand drugs for price setting, the IRA targets those medicines responsible for a disproportionate share of generic industry profits, further undermining the viability of the generics industry

References

- Pub. L. 117-169, https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ169/PLAW-117publ169.pdf. , accessed on December 14, 2024.

- CBO. How increased competition from generic drugs has affected prices and returns in the pharmaceutical industry. July 1998. Accessed at, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/105th-congress-1997-1998/reports/pharm.pdf, on July 31, 2024.

- The U.S. Generic & biosimilar medicines savings report. September 2023. AAM-2023-Generic-Biosimilar-Medicines-Savings-Report-web.pdf (accessiblemeds.org), accessed on June 28, 2024.

- Long, D. 2023-2024 Health care and pharmaceutical marketplace trends (April 2024) IQVIA.

- Grabowski H, Long G, Mortimer R, Bilginsoy M. Continuing trends in U.S. brand-name and generic drug competition. J Med Econ. 2021 Jan-Dec;24(1):908-917.

- https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2022-annual-report

- https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/drug-shortages-in-the-us-2023

- KPMG Generics 2030: Three strategies to curb the downward spiral. Generics 2030 (kpmg.com), accessed ono June 28, 2024.

- FDA. Hatch-Waxman Letters. February 3, 2022. Hatch-Waxman Letters | FDA, accessed on June 28, 2024.

- FDA. Generic Competition and Drug Prices: new evidence linking greater generic competition and lower generic drug prices. December 2019. Accessed on June 28, 2024.

- Cubanski J. Explaining the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. KFF January 24, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/#, accessed on June 28, 2024.

- Rome BN, Lee CWC, Gagne J, Kesselheim AS. Factors associated with generic drug uptake in the United States, 2012 to 2017. Value Health. 2021; 24(6):804-811.

- Cohen, J. Inflation Reduction Act favors biologics over small molecules: in the long term, this could partly undermine Bill’s effort to contain costs. Forbes, January 15, 2023 Inflation Reduction Act Favors Biologics Over Small Molecules: In The Long Term, This Could Partly Undermine Bill’s Effort To Contain Costs (forbes.com), accessed on June 28, 2024.

- O’Brien JM, et al. How the IRA could delay pharmaceutical launches, reduce indications, and chill evidence generation. Health Affairs, November 3, 2023. How The IRA Could Delay Pharmaceutical Launches, Reduce Indications, And Chill Evidence Generation | Health Affairs, accessed on June 28, 2024.

- Fein A. Surprise! Thanks to the IRA, Part D plans will prefer high-list, high-rebate drugs. February 21, 2024. Drug Channels. Accessed at: Drug Channels: Surprise! Thanks to the IRA, Part D Plans Will Prefer High-List, High-Rebate Drugs, on June 28, 2024.

- Policy Statement of the Federal Trade Commission on Rebates and Fees in Exchange for Excluding Lower-Cost Drug Products. Accessed at: Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies (ftc.gov), on September 16, 2024.

- Payer Perceptions of the Inflation Reduction Act. Lumanity Payer Insights Panel. August 28, 2023.

- Gaudette, E., et al. Competition in international drug markets. JAMA Health Forum. 2024;5(10):e243391. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.3391.

- Association for Accessible Medicines. Drug Shortages: Causes & Solutions. Accessed at: AAM_White_Paper_on_Drug_Shortages-06-22-2023.pdf, on January 28, 2025.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Shortages: Root Causes and Potential Solutions. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed at: 2019 Drug Shortages Report, Updated February 21, 2020, on January 27, 2015.