Background

Companies can now apply to the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for a marketing authorization using the international recognition procedure (IRP). This procedure allows medicines to be approved based on the assessment reports from trusted international regulatory authorities, or reference regulators.

As the key body involved in health technology assessment (HTA) in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) aims to publish their final guidance within 90 days of the marketing authorization being granted – using the IRP allows companies an opportunity to launch their medicine in the UK earlier. In October of this year, NICE provided advice on the implications of this accelerated approval route for their assessment.1 While accelerated access is typically desirable for both patients and manufacturers, it will often have implications for the depth of evidence available to support the new technology’s clinical and cost-effectiveness.

In this report, we briefly summarize NICE’s advice, then consider the advantages and disadvantages of seeking earlier marketing authorization via the IRP, from the manufacturer’s perspective.

Summary of NICE’s advice

NICE provided advice on the implications for the manufacturer under five different scenarios.

We consider their third scenario (where regulatory approval is on the basis of a single-arm study) to actually cover two distinctly different scenarios: when a future RCT is planned for the future and when it is not planned for the future. We therefore split this scenario into two.

In each case, before summarizing NICE’s advice for each scenario, we attach our own “handle” for that scenario – providing a brief indication of its likely implication for the manufacturer. After summarizing NICE’s advice, we go on to consider the consequences and opportunities for the manufacturer of going earlier versus later.

The UK’s new IRP pathway for marketing authorization

NICE’s advice to manufacturers

Contact us

Contact us to learn more about how Lumanity can help you navigate the IRP pathway for optimized market access.

1. The “safe” option

IRP route leading to appraisal with the final analysis of the pivotal RCT

NICE encourages companies to consider using the IRP and proceed with a NICE submission promptly after the first regulatory approval by another reference regulator, provided that:

- NICE is notified of these intentions 24 months prior to the expected submission;

- The company can complete the evidence submission in line with the NICE manual;

- Final analysis of the pivotal randomized controlled trial (RCT) is available;

- The trial population and comparators are appropriate and broadly in line with the expected UK National Heath Service (NHS) population; and

- The trial endpoints are appropriate or have been substantially validated.

2. The “bold” option

IRP route with primary/interim RCT data + managed access agreement to seek accelerated access

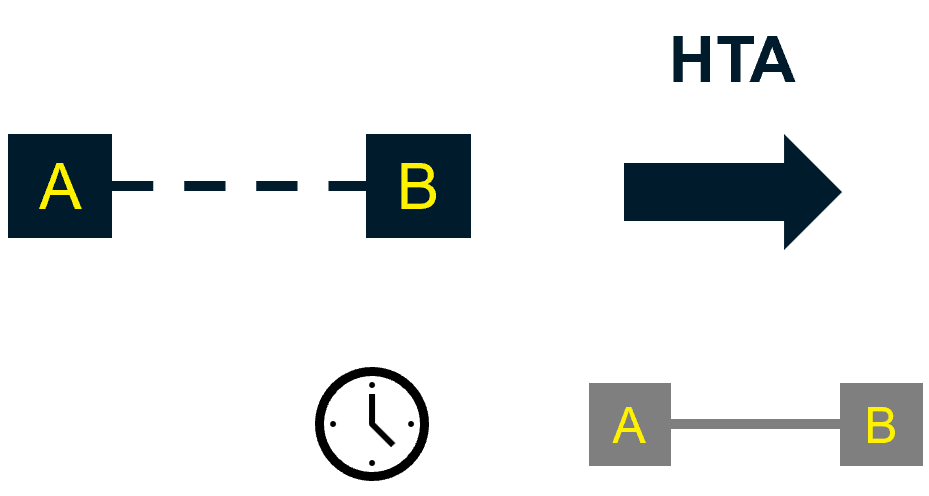

If the regulatory approval is based on a primary or interim analysis of the pivotal trial, and if further analyses are expected in the future, then the intervention will likely be a good candidate for managed access.

This means the company will need to consider a further discount for the duration of the managed access – and risk this additional discount likely being “locked in” beyond into routine access.

3. The big move

IRP route to seek approval based on single-arm study, where conventional route would be based on RCT

If the regulatory approval is based on a single-arm study, and if an RCT is being planned for the future, then the intervention could be considered a candidate for managed access.

This way, the company gains UK access before any RCT data are available for inclusion in HTA. However, in this scenario, the manufacturer is at risk of permanently locking in a notably bigger discount than if they submitted later.

4. Pursuing NICE approval on the basis of a single-arm study

A common scenario

If regulatory approval is based on a single-arm trial, and an RCT is not being planned or undertaken in the future, NICE suggests the company consider whether the data available at the time of regulatory approval are sufficient for HTA.

NICE also uses this opportunity to point to their Technical Support Document 172, as best practice for creating a synthetic control arm – a step that may be considered appropriate as part of NICE’s technology appraisal process.

5. Pursuing NICE approval using an RCT with the “wrong”

comparator

A common scenario

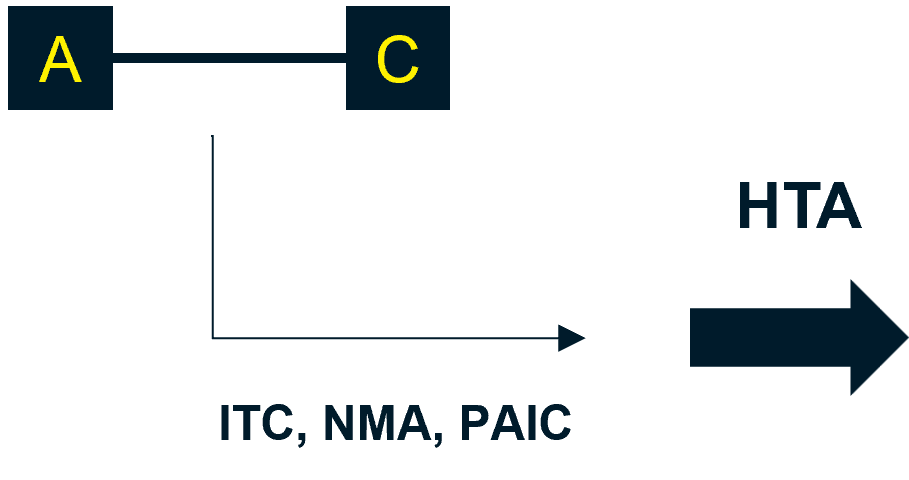

If the trial population or the comparators used in the pivotal trial do not align with UK practice, indirect treatment comparison (ITC) and/or network meta-analysis (NMA) methods should be used, supported with real-world evidence where available.

NICE recommends that unanchored population-adjusted indirect comparison (PAIC) and/or unanchored methods using patient-level data (PLD) from clinical trials should only be considered when there is not a connected network of trials.3

6. Pursuing NICE approval with a trial using a non-validated primary

endpoint

A common scenario

In some disease areas, clinical trials will use a primary endpoint that may not reflect clinically important outcomes. If regulatory approval has been based on a non-validated endpoint, then this may present a challenge during HTA. The extent to which this disrupts a technology appraisal will depend on the following:

- Which secondary outcomes are included in the trial;

- How the trial data are used in an economic model;

- What assumptions are required; and

- The medicine’s value proposition.

The company will need to carefully consider the necessary assumptions between the drug effect on the trial endpoint and the longer-term outcomes of clinical relevance to the patient.

NICE (and other HTA organizations) expects to launch guidance on using surrogate outcomes in cost-effectiveness analysis later in 2024.4

Earlier versus later: what are the consequences for the manufacturer?

The opportunity to launch earlier is almost always positive. A faster launch allows more patients to benefit, as well as typically giving the manufacturer greater market share. An early launch (provided by the IRP route) might also enable a novel technology to be the first in its class to market – likely providing a very substantial commercial advantage relative to it being perceived as a “me-too” technology, which may occur if it launches as second, third, or even fourth to market.

However, this potential for earlier launch does come with the potential consideration of whether the evidence base is sufficiently established to navigate NICE’s extremely rigorous HTA process. Ultimately, NICE’s data requirements and methods will remain the same, regardless of the marketing authorization route.5 Uncertainty is a key consideration for NICE when assessing how to apply the cost-effectiveness threshold. Triggering a faster assessment may notably increase the risk that NICE is only willing to pay £20,000 (rather than £30,000) for each quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

“Ultimately, NICE’s data requirements and methods will remain the same, regardless of the marketing authorization route… uncertainty is a key consideration when assessing how to apply the cost-effectiveness threshold.”

When navigating a NICE submission with a less-established evidence base, managed access routes such as the Innovative Medicines Fund (IMF) and the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) present – in principle – ideal options for NICE, NHS England, and the manufacturer to manage the additional uncertainty that results from this scenario. However, if the technology is covered by the IMF/CDF, the reimbursed price of the technology will almost certainly undergo a further discount to account for the increased uncertainty. When the novel technology is re-assessed at the end of the managed access process, the price of the technology could rise if the more established evidence base supports a higher value.

Manufacturers are understandably skeptical about whether NHS England will ever grant such a price rise. Our experience of CDF exits indicates this skepticism is justified; any discount granted to access the IMF/CDF is likely to be permanent.

“We need to launch as soon as possible – how can we mitigate the risks?”

Whether it be for accelerating patient access, accessing sales revenue as early as possible, or beating a key competitor to the market, sometimes manufacturers will need to go early and accept the permanent discount that will likely result from navigating NICE with a less established evidence base. Below are some starting suggestions on how manufacturers can minimize the risk of either a negative appraisal or NICE “discounting away the uncertainty”:

1. Evaluate in depth any NICE appraisals previously undertaken in your novel technology’s therapy area/indication.

- What evidence did they have available for their submission?

- What precedent was established for evidence, disease characteristics, and wider assumptions that are likely to be key to a cost-effectiveness model?

2. Consider how your “IRP approval route” evidence base stacks up to that of any prior appraisals.

- Is your evidence base similar or notably less established?

- If less established, which elements are primarily affected – for example, absence of a comparator arm, or shorter trial follow-up?

- Is there a way to utilize the prior appraisal’s more established evidence base?

3. Develop an early cost-effectiveness model to identify your justifiable price.

- Which model parameters have the greatest influence on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio?

- What would be the impact of NICE insisting on more pessimistic assumptions for the parameters for which your evidence base is particularly sparse?

- How different is the justifiable price likely to be if: a) you had the data to defend more optimistic assumptions for these parameters; and b) the threshold was £30,000 per QALY rather than £20,000 per QALY?

4. Align with key external and internal stakeholders.

- How much clinical demand will there be for the novel technology if you launch with the less-established evidence base?

- How much clinical support exists for the more optimistic assumptions you need to adopt in the model because of the sparser evidence?

- Do key opinion leaders (KoLs) have access to any wider data sources that could support these assumptions?Would formal elicitation methods lead to parameters that support your case?

- Are your global and cross-functional colleagues aligned on the priority activities you need to undertake to mitigate risk and the likely price point needed to gain NICE approval?

5. Develop your evidence generation plan and lay the groundwork for the managed access route.

- Is going via the CDF/IMF likely to be critical to get an initial “Yes” from NICE? If so, which areas of uncertainty will be addressed over the course of the managed entry period?

- Which key areas of uncertainty can you meaningfully address ahead of the initial NICE appraisal?

- Ahead of NICE’s initial appraisal, can interim evidence (registry data, structured expert elicitation) be used to avoid locking in conservative assumptions during the initial appraisal, given that the consequence for price is unlikely to be reversed?

6. Weave a narrative in the initial submission that has strong external support.

- How can you knit together precedent, existing trial evidence, your supplementary evidence, and patient and KoL support to ensure the value of your novel technology is best understood?

- How should the dossier and its evidence be framed so that any perception of uncertainty is minimized and any further evidence being collected during managed entry arrangements would simply be embellishment to the existing evidence base?

Everyone wants patients to have faster access to truly innovative medicines. The IRP regulatory pathway has a key role to play in enabling this critical objective. We can play our part in ensuring the accelerated regulatory approval leads to NICE approval, reimbursement, and ultimately patient access by intelligently considering the reimbursement context; the novel therapy’s expected evidence base; any prior NICE precedent; and the supplementary evidence that will support effective decision-making.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Implications of using the international recognition procedure (IRP) for a NICE technology appraisal evidence submission. 2024. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/our-programmes/technology-appraisals/implications-of-using-international-recognition-procedure-for-a-nice-technology-appraisal-evidence-submission.docx. Accessed: 27 November 2024.

- Faria R, Alava MH, Manca A and Wailoo AJ. TSD 17: The use of observational data to inform estimates of treatment effectiveness in technology appraisal: Methods for comparative individual patient data. 2015. Available at: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nice-dsu/tsds/observational-data. Accessed: 27 November 2024.

- Phillippo DM, Ades AE, Dias S, et al. TSD 18: Methods for population-adjusted indirect comparisons in submissions to NICE. 2016. Available at: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nice-dsu/tsds/evidence-synthesis. Accessed: 27 November 2024.

- Bouvy J. How ‘surrogate outcomes’ influence long-term health outcomes. 2023. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/blogs/how-surrogate-outcomes-influence-long-term-health-outcomes. Accessed: 27 November 2024.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE health technology evaluations: the manual. 2022. (Updated: 31 October 2023) Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/resources/nice-health-technology-evaluations-the-manual-pdf-72286779244741. Accessed: 27 November 2024.