Authored by Jeff Bockman, Cello Health BioConsulting, now part of Lumanity

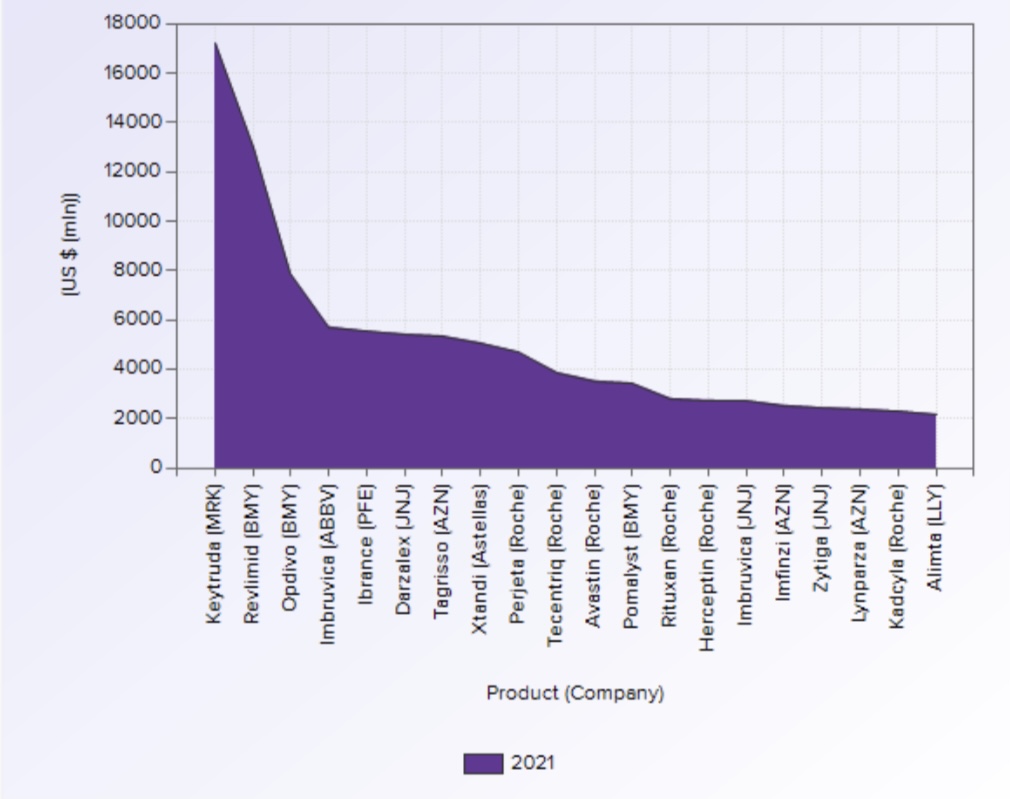

I got to thinking recently about the push towards developing drugs for molecularly stratified patient populations, including a spate of approvals over the past few years for agents targeting aberrantly expressed (mutated, translocated, amplified, etc.) proteins, as opposed to many of the blockbuster drugs (based on WW sales — see data, right, from EvaluatePharma) that are not “precision medicine” agents.

Of course, two of the top selling drugs are Keytruda and Opdivo that, while having some approvals in MSI-hi cancers, and notwithstanding the relevance of PD-L1 and TMB levels, are by and large broadly utilized, foundational agents. And they are certainly transformative agents, albeit not for all cancers or all patients. Revlimid, the second most selling drug, has no such biomarkers at all.

This then got me thinking about chemotherapy and radiotherapy, that are still key components in management of the majority of cancers, And how language itself can be so imprecise. We all tend to make a dichotomy between chemo and “targeted” oncology agents, and yet taxanes are very targeted, antimetabolites are very targeted. And are PARP inhibitors or other DDR agents, while targeted, and while showing optimal efficacy in mutated patients, not in many ways cytotoxic agents, which we have tended to equate with broadly acting chemotherapy?

While these musings may seem obvious to those focused in Oncology, for those not, especially patients, this is not purely academic. Language shapes attitudes. The term “chemotherapy” sends shivers down most people’s spines. “Targeted therapy,” however, conjures a quite different reaction.

But even we in the field are often imprecise, even sloppy, with our terminology, leading to misunderstandings, but maybe even to actually thinking incorrectly about how to develop a new therapy, how to position it. Just now the way I have used “targeted therapy” in juxtaposition against chemotherapy suggests, falsely, some halo of safety and tolerability that may not be there (regorafenib, if I need to cite an example).

I am not suggesting as George Orwell laments in Politics and the English Language that we are intentionally obfuscating. But I do sometimes fear that phrases like “precision oncology” or “targeted therapy” are a bit like “rectification of frontiers” that Orwell lambasts in his essay.

Just some stormy Thursday afternoon musings…

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms…”

George Orwell, Politics and the English Language