Authored by BresMed, now part of Lumanity

No matter how robust in design, clinical trials can never fully address the uncertainty surrounding the comparative effectiveness and safety of a novel product in the real world. This is particularly pertinent in rare diseases for several reasons: small sample sizes and heterogeneous populations create challenges in demonstrating clinically significant benefits, randomized head-to-head comparisons are often unfeasible or unethical, and relationships between measurable trial endpoints and patient-relevant outcomes are under-studied and poorly understood. When preparing for health technology assessments and reimbursement discussions for a rare disease product, we believe that it is both feasible and advisable to anticipate and subsequently minimize the key uncertainties before starting the later phases of clinical programs. While this is not a new proposition, our experience suggests that this rarely happens in practice, and there is therefore a need to reinforce the value of this simple recommendation.

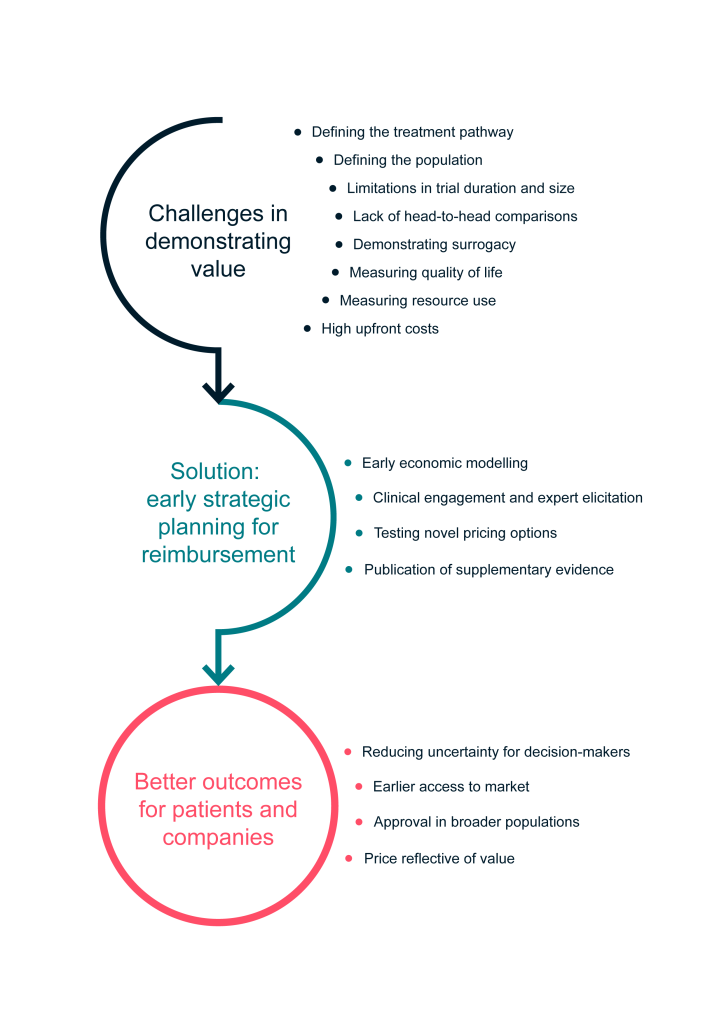

In this white paper, we outline eight key challenges that manufacturers face when demonstrating the value of rare disease products to decision-makers, and set out our framework for proactively overcoming these challenges. Using this framework, we believe that manufacturers can achieve earlier access to market, at a price that reflects product value.

Common challenges in demonstrating value for drugs for rare diseases

Unclear treatment pathways

Poorly defined populations

Trials limited in duration and sample size

Lack of head-to-head trial data

Weak surrogacy relationships between trial outcomes and how patients feel, function and survive

Lack of appropriate quality-of-life instruments and difficulty measuring quality of life

Unclear impacts on costs and services provision

Risk-sharing through innovative pricing mechanisms and coverage with evidence development

1. Unclear treatment pathways

Summary Many rare diseases have no existing disease-altering treatments. In these cases, current treatment is often symptomatic, variable and unknown. This creates problems in demonstrating the effectiveness of a new drug for a rare disease compared with an unspecified current comparator. Working closely with clinical and patient experts through formal processes can define pathways and create consensus where none previously existed.

Demonstrating relative benefit in a health technology assessment (HTA) requires two elements: assessing what the new treatment achieves, and assessing what would happen in its absence (i.e. the current experience). Rare diseases frequently lack effective treatments and clear, if any, clinical treatment guidelines. This leads to variations in treatment paradigms between and within jurisdictions, occasionally including the use of off-label products, as well as uncertainty as to how patients are currently treated. Thus, when making a value case for a treatment of a rare disease, half of the necessary data are often missing.

This situation creates challenges for manufacturers in demonstrating the relative gains their treatment will provide and the relative costs that will be incurred. The manufacturer of a novel agent – particularly if it is the first in a therapeutic area – can play a key role in galvanizing clinical opinion leaders and patient groups via advisory boards, structured surveys and other mechanisms so as to obtain enough evidence for a comparison to take place. Where no consensus exists, this can be shaped using expert elicitation techniques such as the Delphi method and the Sheffield Elicitation Framework (SHELF).1

2. Poorly defined populations

Summary A ‘clinically distinct’ population with clearly defined characteristics must be identified as the target for treatment and, if necessary, its uniqueness justified. It is crucial to understand and perhaps influence how this population could be diagnosed, how it will be diagnosed in practice, and who will bear the costs of any changes to the diagnostic process. Again, working with clinical and patient groups in a systematic way may be key to addressing these issues.

In recent years, several HTA agencies worldwide (including the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review [ICER] in the US, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] in England, the Scottish Medicines Consortium [SMC] in Scotland and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee [PBAC] in Australia) have imposed less stringent evidence requirements for drugs for rare diseases (DRDs), with the aim of rewarding investment sufficiently in those areas. However, these agencies have all resisted any temptation by manufacturers to ‘salami-slice’ more common conditions into several categories of disease that would each individually be defined as ultra-rare.

Under NICE’s Highly Specialised Technologies (HST) process2 and the PBAC’s Life Saving Drugs Program (LSDP)3, drugs are only eligible if the target patient group is clinically distinct. NICE’s definition of ‘clinically distinct’ is unclear, whereas the LSDP guidance specifies that diseases divided by causative mutation, genetic subtype or treatment stage cannot be considered distinct. It is therefore important for manufacturers to consider what makes the target population clinically distinct and how this affects the eligibility of a product for rare-disease-specific HTA processes, and to do so as early as possible.

A concomitant of the need to define a clinically distinct population as eligible for treatment is to indicate how this population may be defined in practice. If this has never been done before, the manufacturer will need to elucidate – with sufficient clarity to satisfy the HTA agency – both how this can be done technically and the resulting organizational implications, and this may be a significant task. Once again, partnership with clinicians and patients is crucial in solving these problems.

The question of who will bear the costs associated with any required organizational changes to the diagnostic work-up may be a decisive issue. The best approach for addressing this is likely to differ between jurisdictions depending on the state of advancement of the science locally and on payer policies. A tailored suite of evidence generation is often necessary, based on an early understanding of:

- Markets (payer rules and attitudes; current diagnosis and treatment patterns)

- Therapeutic area (how the disease progresses with/without the technology; basic science; clinical evidence; input from patient groups)

- Evaluation/pricing mechanisms

While this is also the case for more common diseases, with rare diseases there can be a paucity of evidence for these topics in the scientific literature, and thus more time may be required to adequately address these issues.

3. Trials limited in duration and sample size

Summary

Clinical trials investigating DRDs are often associated with several limitations that result in a high level of uncertainty with respect to long-term safety, effectiveness, and comparative effectiveness. An early exploration of complementary sources of evidence, plus an understanding of the acceptability of this complementary evidence in the past by decision-makers, will allow the best available evidence to be incorporated into the value proposition in order to reduce uncertainty.

Rare diseases pose several challenges to trial design. For example:

- Low prevalence leads to small sample sizes

- Desire for early access to treatment where none existed previously means that patients are not willing to receive standard of care for long, leading to short trial durations and high levels of crossing over in controlled trials

- Patient populations are often heterogeneous, creating challenges in demonstrating clinically significant benefits

Dealing with these challenges raises questions concerning the following:

- The patient and payer relevance of outcome measures, which should be chosen to show a significant response in a small trial (see Challenge 5)

- The absence of statistical techniques that can reliably be applied in small populations where most or all eligible patients choose to cross over

- Trial populations that are too small for the effect of covariates on efficacy to be analyzed

- Trials that are too short in the context of long-term (and perhaps life-long) effects

- Uncertainty about dosing

These problems may create a degree of uncertainty that reimbursement decision-makers are unwilling to accept.

There are no simple, ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions here; it is clear that what is needed is the highest possible standard of statistical sophistication in using and interpreting the data from the trial, together with material from real world evidence and from systematically collected guidance from clinicians. Deciding as early as possible how the value case will be made maximizes the time available to identify evidence gaps to fill as a priority, implement appropriate research methods, and subject novel evidence to peer review prior to HTA submissions. The fact that submissions will likely be made in many jurisdictions adds a further layer of complexity to the process, requiring an understanding of the formal and informal processes of evaluation in multiple countries.

4. Lack of head-to-head comparison trial data

Summary Head-to-head comparisons with relevant comparators are not always feasible for DRDs. The following should be considered at an early stage: current treatments and likely comparators; techniques for achieving the best comparison possible and identifying limitations of the empirical evidence; and the construction of a synthetic comparator arm with testing of its inherent variability. This will allow time to explore methods and key covariates, and to maximize the reliability of requisite statistical analyses.

As a result of low patient numbers, high burden of disease, and ethical and patient preference considerations, trials in the rare disease space are often necessarily single arm in design. Nevertheless, HTA agencies do not look kindly on such designs when they believe a comparative trial was possible.

As is the case with small comparative trials, both statistical sophistication and the use of sources of data outside the trial itself come to the fore. One possible approach is to effectively simulate a comparison with the existing mix of treatments. The work that supports understanding the patient pathway (see Challenge 1) can, with some extension, be used to create a natural history comparator arm for modelling purposes. Alternatively, if there is a candidate treatment that provides a comparator at a particular point in the patient pathway such that, for example, relative hazard ratios need to be estimated, then a matching-adjusted indirect comparison (or MAIC) or a similar statistical technique may be employed to utilize published data. A better approach, if possible, is to obtain and use patient-level data from registries or other sources. In this case, exploring the generalizability and potential biases of a broad range of alternative evidence sources, and addressing these concerns with statistical methods, can improve the value case.

Where no head-to-head comparison with key comparators is feasible, it is particularly important to anticipate the need for statistical analysis and ensure that evidence on key covariates is captured in the trials themselves. This should ideally be informed by early consideration of the covariates that have been identified in the literature and by interviews with clinicians. While decision-makers can be sceptical about the use of statistical methods to adjust non-randomized data, this is usually superior to presenting a naïve comparison where known biases exist.

Once again, leaving these considerations until close to launch may mean that problems remain that could have been solved, or that solutions are not readily accepted because there has not been time to submit them to peer review.

5. Weak surrogacy relationships between trial outcomes and how patients feel, function and survive

Summary Due to small patient numbers, short trial durations and an absence of instruments to measure patient-relevant outcomes, it may be the case that, out of necessity, registration trials use outcome measures that tell us nothing directly about the value of the treatment to patients (and therefore payers). Work must be started early to identify measures for inclusion in a trial that balance clinical validity with external data availability and can be linked to product value. If the value story is to rely on a newly established relationship, it must be published before it is used in HTA submissions.

The endpoints explored in clinical trials for DRDs are often not directly and obviously relevant to patients. Commonly, biomarkers are chosen by regulators because they are most likely to allow a statistically significant impact of the new treatment to be demonstrated. Other options, closer to patients, include common measures of function (e.g. 6-minute walk test) and novel or modified composite scoring systems that attempt to capture multiple domains of complex and heterogeneous diseases.

However, the relevance of such measures to patients may only be partial (for example, once patients are non-ambulant, the 6-minute walk test becomes useless), and the comprehensiveness and scalar properties of many scales make demonstrating benefit very liable to chance. A trial endpoint is more likely to be an acceptable surrogate for patient-relevant outcomes – such as patient function, quality of life and survival – if its relationship to these outcomes has been explored and demonstrated publicly before a trial reads out.

Guidance from Australia’s PBAC4 and Germany’s Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG5) both outline steps that manufacturers can take to allay the concerns of decision-makers in establishing surrogacy relationships. Ideally, these steps should be considered before selecting both primary and secondary endpoints in a trial. While it may be challenging in the case of DRDs to meet all of the recommendations laid out in the guidance, several steps can be taken to optimize the evidence base. Available trial data and wider literature should be explored with the following hierarchy of evidence in mind6, 7:

- Level 1: Treatment effect on surrogate outcome corresponds to treatment effect on patient-relevant outcomes

- Level 2: Association between surrogate outcome and patient-relevant outcomes

- Level 3: Biological plausibility of relationship between surrogate outcome and patient-relevant outcome

This can be achieved via complementary use of statistical analysis of randomized controlled trials and real world evidence, literature reviews, and structured expert elicitation1, ideally using a combination of empirical evidence and expert opinion where possible. Evidence directly relating to the condition and intervention of interest is favored by decision-makers, though supportive evidence from conditions with similar pathophysiology and interventions with a comparable mechanism of action may be valuable to strengthen the argument. Any findings should be published before HTA and pricing and reimbursement discussions take place to give the analysis credibility and to meet the requirements of some agencies.

Once again, consideration of the appropriate outcomes to include in the trial – not just for marketing authorization, but for reimbursement and pricing – must start early to avoid the risk of being unable to include the outcome on which you need to rely for your value case. Outcome measures have to support modelling and, to this end, may need to be supported by suitable real world evidence, but they also need to have been demonstrated to relate to how patients feel and function, and thus to payer value.

6. Lack of appropriate quality-of-life instruments and difficulty measuring quality of life

Summary Capturing accurate quality-of-life data for DRDs for the patient or caregiver is often fraught with challenges due to small sample sizes, heterogenous and young populations, cognitive and other debilitating effects, and absence of existing disease-specific measures. Considering this early on and working closely with clinical and patient experts can allow many of these challenges to be overcome.

Rare diseases, particularly rare genetic conditions that affect children, commonly carry a high disease burden to both patients and caregivers. Evidence on the effects of a treatment on the quality of life of patients (and sometimes caregivers2, 8) is desired by most HTA agencies, even those that do not embrace the quality-adjusted life year (or QALY) as a metric.

However, such evidence is not easy to obtain. Small sample sizes and short trial durations mean that demonstrating changes with disease-specific instruments is often impossible, and this problem is likely to be worse with generic measures of health-related quality-of-life, such as the EQ-5D® or the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Furthermore, the changes in health-related quality of life that are important in demonstrating value are commonly those that occur outside of a trial period, perhaps over many years, for transformative treatments in diseases that affect the young. Finding or creating a measure that can be useful in that context is often a very important step in demonstrating the value of a new treatment, and one that is almost as often neglected by companies bringing products to market.

Manufacturers should consider how they will capture quality-of-life evidence early in their process of planning and whether to capture the effects on caregivers as well as patients. Literature reviews as well as alliances with patient groups, clinical key opinion leaders and academics can all play a role here, particularly if a decision is made to construct a new instrument, for example, by conducting qualitative interviews, a vignette study or a discrete choice experiment. If this is not possible, there may be an analogous disease area from which utilities could be derived. Obtaining clinical input on the generalizability of these data to the population of interest can provide important context.

7. Unclear impacts on costs and service provision

Summary Where no existing therapies are available for a rare disease, capturing existing costs can be challenging. The introduction of a new treatment may require a reorganization of service provision, which can disincentivize decision-makers. These aspects should be adequately explored by manufacturers through engagement with clinical and patient experts, well before any submission to an HTA agency.

Understanding the impact on healthcare resource use is critical in building a cost-effectiveness case, and, increasingly, indirect costs are also being considered by decision-makers for ultra-rare diseases.2,8 However, as noted above, treatment pathways for rare diseases are often heterogeneous and poorly publicized. Furthermore, where existing targeted therapies are lacking, the emergence of a novel product for a rare disease (particularly more complex treatments such as gene therapies) could require a step-change in the way the service is provided. This may result in disincentives for payers to introduce new products, despite the benefits they may offer to patients.

Where healthcare resource use data are absent from clinical trials, estimates can be obtained through literature reviews focusing on the indication of interest or analogous indications and through expert elicitation exercises in each relevant jurisdiction, probably tied to the process described earlier for defining the patient pathway. Though clinical experts are an important source of information to understand in-hospital costs, the full cost of a condition cannot be captured without also consulting patients and their caregivers, as many of the costs will be borne by them. Patients and caregivers who have experience of receiving the new drug can also prove a valuable source of evidence for the impact the new drug is likely to have on these costs, which can strengthen the value proposition. Furthermore, where a drug is likely to result in a reorganization of service provision, manufacturers should consider the costs of funding aspects of care that need to be introduced from scratch (e.g. a homecare service), as it may be worthwhile to fund this in return for reimbursement.

8. Risk-sharing through innovative pricing mechanisms and coverage with evidence development

Summary Higher uncertainty at the time of HTA because of accelerated access mechanisms, coupled with the temporal disconnect between costs and benefits sometimes associated with DRDs, can prevent traditional pricing mechanisms from being fit for purpose. Manufacturers being open to and prepared for outcomes-based pricing and coverage with evidence development agreements can smooth the HTA process and decrease time-to-market.

The incentivization of the development of DRDs through accelerated access and premium prices has contributed to relatively rapid patient access to several novel life-changing products. However, this accelerated access has also resulted in increased uncertainty around the time of decision-making and concerns about long-term affordability. Furthermore, for more advanced therapies such as gene therapies, there is often a disconnect between the timings of costs (large and up-front) and benefits (large and long-term). Thus, existing payment mechanisms may not be suitable for all DRDs. More recently, decision-makers have proposed alternative managed access arrangements, involving innovative pricing mechanisms and/or coverage with evidence development to manage risk and reduce uncertainty.

In these circumstances, manufacturers should be open to the idea of sharing risk by linking payments to outcomes or conducting further research post-marketing to help reduce uncertainty. Where some form of coverage with evidence development is planned, the whole suite of evidence generation, both pre- and post-marketing, should be planned as one to ensure that this is cohesive and as complete as possible.

Framework for demonstrating the value of DRDs

Start preparing for reimbursement early with a clear value case in mind

Given the unique challenges in demonstrating the value of DRDs, it is necessary to take a considered and creative approach to evidence generation beyond the clinical program and invest in building relations with key opinion leaders. Of course, not all the challenges outlined in this paper will be relevant to every jurisdiction, product, and disease area.

As a result of these nuances, there is no ‘off-the-shelf’ solution to value demonstration for DRDs. However, regardless of the specifics of the case, we believe that it is both feasible and advisable to anticipate the challenges that are likely to play a key role in decision-making, before initiating the later phases of clinical programs.

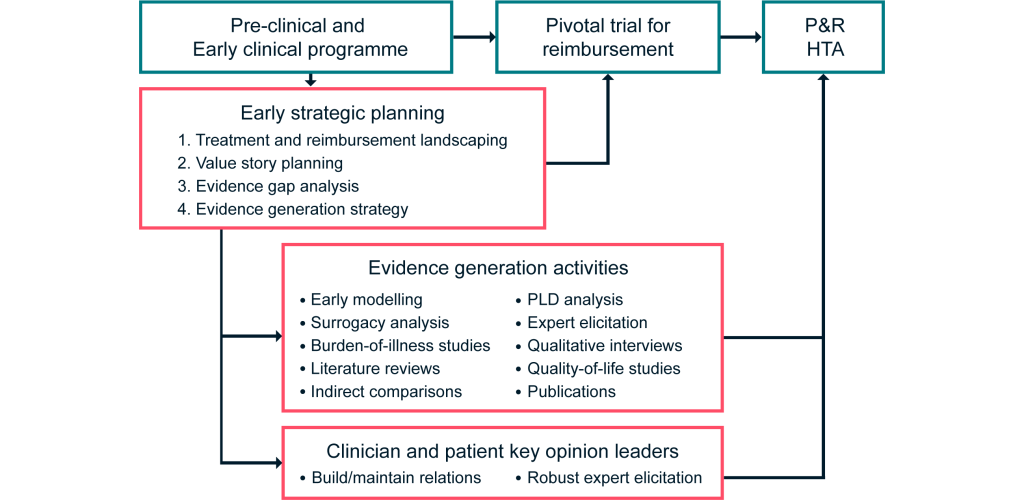

To this end, a bespoke early strategic planning process as outlined in Figure 1 is essential to optimize the evidence base and minimize uncertainty for decision-makers. This can be achieved through carefully considering the requirements in target markets to identify evidence needs, contrasted against the evidence likely to be available from the proposed clinical trial program and broader evidence base.

Figure 1: Our framework for demonstrating the value of DRDs

How early?

Initiating this process early in the clinical programme is strongly advised, as it allows many of the inevitable issues to be proactively addressed and tested through appropriate evidence generation activities. However, the optimal timing will depend on the expected clinical programme for the product of interest.

If it is known in advance that a Phase III trial is planned and will be the pivotal trial for reimbursement discussions, strategic planning for reimbursement should occur before the trial is designed, to allow results to feed in to the trial design. However, in some cases, the full clinical program will not be known in advance. In this instance, strategic planning for reimbursement should occur in the early stages of the Phase II trial to allow sufficient time for supplementary evidence generation and publication before HTA and reimbursement discussions.

What are the risks and benefits?

Early strategic planning as described above is inexpensive relative to the costs associated with mounting trials and therefore carries a relatively low financial risk. We believe this often-overlooked step can result in a large return on investment, through optimization of the evidence base for HTA and reimbursement discussions – thus leading to earlier access to market, approval in broader patient populations, and agreement on a price that reflects product value.

Case study: Project Hercules

Project HERCULES9,10 is an international multi-stakeholder collaboration between Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) charities, healthcare professionals and nine manufacturers, led by Duchenne UK, developing a core suite of patient-focused disease-level tools suitable for HTA in DMD. This project was initiated prior to the companies involved bringing any products to market, and before the initiation of many of their pivotal trials. We have had a continuing involvement in the project from its conception, advising on the necessary activities to allow companies to prepare more easily for submission for reimbursement.

Workstreams include:

- The development of a natural history arm in the form of a model using data from registries, clinical trials and the scientific literature, to provide a comparative base for any single-arm trial results

- A new DMD quality-of-life instrument, already completed and in the process of being developed to provide utility measures for DMD health states

- A burden-of-illness study

- A disease-level economic model for all of the companies to use

Estimating effects on carer quality of life is also being considered.

Project HERCULES is an innovative approach that illustrates aspects of the framework proposed in this document: it is patient-focused, it involves patient groups and clinicians, and it has been made possible through early strategic planning. Its collaborative approach is untypical, but laudable.

Abbreviations

| DRD | Drugs for rare diseases |

| HST | Highly Specialised Technologies (NICE pathway) |

| HTA | Health technology assessment |

| ICER | Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (US) |

| IQWiG | Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Germany) |

| LSDP | Life Saving Drugs Program (Australia) |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (England) |

| PBAC | Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life year |

| SF-36 | 36-Item Short Form Survey |

| SHELF | Sheffield Elicitation Framework |

| SMC | Scottish Medicines Consortium (Scotland) |

References

- Bojke L, Soares MFO, Fox A, et al. Developing a reference protocol for expert elicitation in healthcare decision making. Health Technology Assessment Reports. 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Interim Process and Methods of the Highly Specialised Technologies Programme Updated to reflect 2017 changes. (Updated: April 2017) Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-highly-specialised-technologies-guidance/HST-interim-methods-process-guide-may-17.pdf. Accessed: 26 March 2020.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Procedure guidance for medicines funded through the Life Saving Drugs Program (LSDP). (Updated: July 2018) Available at: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/FD13E541FA14735CCA257BF0001B0AC0/$File/Procedure-guidance-for-medicines-funded-through-the-LSDP.pdf. Accessed: 26 March 2020.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). Report of the surrogate to final outcome working group to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee: a framework for evaluating proposed surrogate measures and their use in submissions to PBAC 2008. 2008. Available at: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/useful-resources/pbac-technical-working-groups-archive/surrogate-to-final-outcomes-working-group-report-2008.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2020.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Validity of surrogate endpoints in oncology. 2011. Available at: https://www.iqwig.de/download/A10-05_Executive_Summary_v1-1_Surrogate_endpoints_in_oncology.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2020.

- Taylor RS and Elston J. The use of surrogate outcomes in model-based cost-effectiveness analyses: a survey of UK Health Technology Assessment reports. 2009.

- Ciani O, Buyse M, Drummond M, et al. Time to review the role of surrogate end points in health policy: state of the art and the way forward. Value in Health. 2017; 20(3):487-95.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Modifications to the ICER value assessment framework for treatments for ultra–rare diseases. (Updated: November 2017) Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ICER-Adaptations-of-Value-Framework-for-Rare-Diseases.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2020.

- Crossley E, Chandler F, Godfrey J, et al. PB4 PROJECT HERCULES: A PATIENT LED PARADIGM IN EVIDENCE GENERATION FOR HTA IN DUCHENNE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY. Value in Health. 2020; 23:S13.

- Powell P, Carlton J, Rowen D, et al. PRO130 PROJECT HERCULES: CONSTRUCTION OF A NEW PREFERENCE-BASED MEASURE OF QUALITY OF LIFE FOR DUCHENNE MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY (DMD). Value in Health. 2019; 22:S865.