In January 2024, the agency responsible for health technology assessment (HTA) in the Netherlands – the Zorginstituut Nederland (ZIN) – updated its guidance for the first time since 2016. We were present at the unveiling of these new guidelines and noticed some significant changes, including our own work on structured expert elicitation (SEE) being cited. Here, we discuss these updates in the context of the overall use of SEE in HTA, and explain what this means for health technology manufacturers seeking reimbursement in the Netherlands.

Why is expert elicitation important?

When evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a therapy as part of HTA, the intervention is typically compared against the current standard of care. As the information needed is usually not available from a single source, multiple data sources are integrated into a single model to make predictions. The quality of these predictions largely depends on the quality of the underlying data, and usage of the highest quality of data is always preferred.

Even if there are no accessible patient-level data, no relevant literature, and no other statistics to calculate/estimate a model parameter, omitting the parameter entirely is never an acceptable option, as it may have unknown effects on the cost-effectiveness of the evaluated intervention. An assumption can be made on the value of the parameter – but there must be reliable evidence to support the choice of assumption.

To reduce uncertainty around these unknown quantities, the new Dutch guidelines1 explicitly state that in such cases, expert judgment must be obtained (in the form of expert elicitation) and presented in combination with sensitivity analyses, both deterministic and probabilistic. This update mirrors recent changes from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which updated its guidance in 2022 to state a preference for using structured methods for eliciting expert evidence. Structured methods were recommended based on the methods used to manage bias and provide an objective measure of uncertainty. The NICE methods guide2 recommends adhering to existing protocols such as the Medical Research Council protocol.

In 2023, Lumanity collaborated with the University of York and the University of Exeter to provide a more practical resource for SEE, including an overview of SEE for healthcare decision-making, some practical ideas for SEE exercises, adaptable R code for analysis, and simple Microsoft Excel® tools for SEE exercises.3 ZIN cites this work in its new guidelines.

There is an important distinction to be made on the type of evidence generated with experts. Expert opinion is qualitative evidence, whereas expert elicitation is quantitative. As most model parameters are numerical, the latter can be more directly used to provide inputs for economic models when alternative sources of information are not available.

What are the key changes to the ZIN guidelines?

The most important changes in the Dutch guidelines when comparing the updated 2024 version1 with the 2016 version4 are the following:

- Expanded clarifications and requirements in the guidelines on expert elicitation

- All medical costs (also those not related to the condition itself) need to be calculated for additional life-years lived. These costs can be calculated with the Practical Application to Include Future Disease Costs (PAID) tool5

- Reference prices have been updated. For example, new prices have been added for care, travel, and loss of productivity, and new societal costs have been added for very specific cases such as the effects of psychiatry on the justice system

- Depending on the disease and the arguments used, the costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) of one informal carer may be included, and the EQ-5D-Y-5L6 can be used to measure quality of life of children

- Discounting of costs has been lowered to 3%, while discounting of health effects (e.g. QALYs or life years [LYs]) remains at 1.5%

- Value of information analysis has become mandatory, with expected value of perfect information (EVPI) as a minimum addition. Expected value of partial perfect information (EVPPI) is also recommended, and both expected value of sample information (EVSI) and expected net benefit of sampling (ENBS) are optional additions

- Guidelines for health technology appraisals in the programming language R have been added. Programmed model code should be accompanied with explanations in R Markdown7, and an explanatory readme file should also be included

What does ZIN now say about SEE?

ZIN has expanded greatly on its 2016 guidance on expert elicitation, which originally comprised a single paragraph and led to confusion in how the guidance was implemented. The new guidelines provide more clarity on how to appropriately conduct SEE, including the need for transparency in reporting (such as the method used, the number of experts involved, and the types of experts contacted) and the need for a reproducible method that allows for validation. A comparison of key points is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Differences in ZIN guidelines on SEE between 2016 and 2024

| Item | 2016 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Method to systematically report | Delphi (for example) | SHELF, Delphi, Cooke (obligatory to use structured method) |

| Expert selection | Report selection procedure of experts | At least five experts, from different locations, KNAW conflict of interest form |

| Methodology | Describe collection of information, reaching of consensus, and analysis of results | Same, also included list in appendix with criteria for what needs to be reported in much more detail |

| Sensitivity analyses | Should be reported | Should be reported: fixed interval method or variable interval method, which can be used to estimate uncertainty (both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses) |

| Key: KNAW, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences); SHELF, Sheffield Elicitation Framework. | ||

New instructions in guidelines

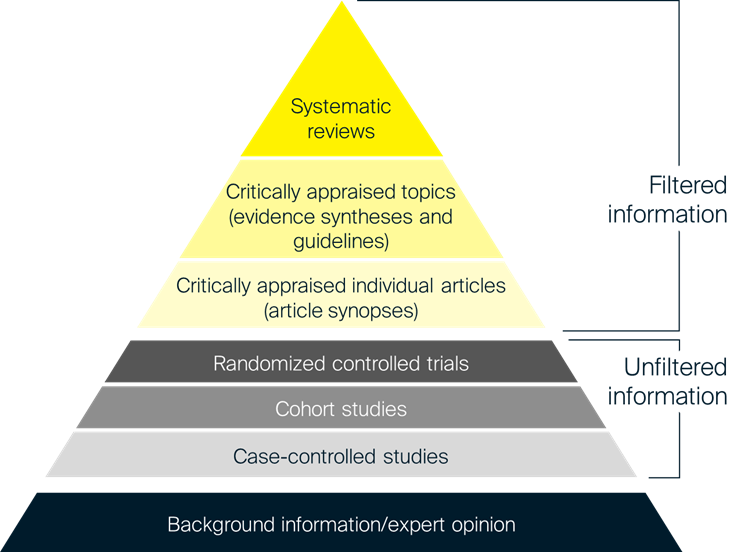

Expert opinion is considered to be the lowest level of evidence, as shown in the pyramid of evidence in Figure 1. The new guidelines recommend only using this option when no other sources of information are available. The guidelines also recommend using as much published data as possible to inform the model. All parts of the model that are informed by expert elicitation must also be subjected to sensitivity analyses, both probabilistic and deterministic.

Figure 1: Hierarchy of evidence

Sources: Adapted from University of Canberra, 20238 and Hoffman et al., 2013.9

The panel should consist of at least five experts, including (but not limited to) clinicians, patients, and informal caregivers of patients. Experts should preferably be from different hospitals, with consideration to regional spread (especially regarding the differences between urban and rural hospitals). Exceptions are possible – for example, in the case of rare diseases, or if the disease is only treated in one specific institute. All panel members should sign a conflict of interest form from the KNAW (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen; Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences). The ZIN’s stated preference is for panel members to be questioned individually, as this allows uncertainty to be measured; however, an advisory board is welcomed as an addition to the expert elicitation.

Notably, it is a requirement now to use a structured method of expert elicitation (i.e. one that involves a process or protocol that is agreed prior to conducting the work), rather than an unstructured method. There are several structured methods for expert elicitation, as outlined in the box below.

An important step in any elicitation exercise is to verify the final results of the elicitation exercise with the experts to ensure that the results are consistent with their judgment. The ZIN guidelines specifically call out this step, so it is important to factor this into the elicitation timelines.

Common methods of SEE

Sheffield Elicitation Framework (SHELF)

In the SHELF method10, a form of behavioral aggregation, participants are engaged in one-on-one interviews to gain their judgments regarding a quantity of interest. Probability distributions are then generated from these judgments and presented together at a group workshop. Here, the participants are requested to discuss the judgments from the point of view of a rational, impartial observer, with the aim of arriving at a consensus regarding a group probability distribution.

Delphi method

The Delphi method11 is a similar approach but it involves a series of online surveys. In each round of the Delphi process, the respondents’ answers to the questions in the previous round are presented to the whole group anonymously, in an iterative manner. In the final round, the participants agree on a consensus judgment. This approach allows the survey participants to provide their knowledge and expertise and gives them the opportunity to amend their responses. The fact that it is conducted anonymously also ensures that the judgments are considered independently of who said them, thus reducing bias.

Cooke method

The Cooke method aims to measure uncertainty through expert opinion, using a type of mathematical aggregation.12 In addition to being asked questions on the topic of interest, participants are also asked a series of calibration questions. These are individually determined based on each participants’ field of expertise, using data and reports that are not publicly available. The participants are then given scores according to the accuracy of their calibration answers, which are then used to generate performance-based weights for their topical answers. The individual probability distributions are averaged and weighted based on performance to arrive at a final distribution. Due to the complexity of conducting this type of method, it has seen limited use in healthcare settings.

STEER

While not explicitly mentioned in ZIN’s guidance, STEER is an approach related to the SHELF method:

“The STEER method … involves conducting one-to-one interviews or an online survey to gather judgments about a particular quantity of interest… After this step, at the final stage, individual probability distributions are averaged (either unweighted or weighted based on expert performance) to reach a final probability distribution – a process known as ‘mathematical aggregation’.”3

Requirements for reporting expert elicitation

The ZIN guidelines specify the key reporting requirements for expert elicitation, which are consistent with the existing guidelines for expert elicitation (as well as good practice for any well-run project). Briefly, these can be summarized as the following:

- Provide a clear justification for the expert elicitation and demonstrate that empirical evidence is lacking

- Define the question (quantity of interest), which requires expert elicitation, as a necessary one. Assigning probabilities to a quantity of interest in the form of subjective judgment is inherently difficult. Therefore, effort is needed to define specific, simple, observable, and time-bound parameters to avoid confusion among experts

- Carefully choose the parameter type and describe it fully. This can be challenging in health economics as key drivers in cost-effectiveness models are often complex and interdependent (e.g. survival). Research conducted in the UK13 suggests using intuitive outcomes, such as median survival, when deciding on the quantities and parameters to explore through expert elicitation

- Clearly describe and justify the method chosen for expert elicitation. Options mentioned by ZIN include SHELF, the Delphi method and the Cooke method. However, other methods may be used once clearly justified

- Demonstrate how the appropriate experts were identified and recruited. This is important to ensure that the elicitation was conducted robustly. As most experts are unfamiliar with structured elicitation, and to enhance their skills and reduce bias, relevant training should be provided to experts before the elicitation task

- Experts can be selected based on standard criteria such as their relevant clinical experience, recognition within their peer networks, and their willingness to participate. Additionally, their normative skills may also be taken into consideration, given the challenging nature of the elicitation process. The number of available experts, the level of variation expected among the experts, and budget and time constraints can play a role. As a guide, SHELF recommends between four and eight experts10, while STEER suggests a minimum of five3

- Include the relevant information for decision-makers to objectively evaluate the elicitation. The results of the elicitation should be clearly described, especially any disagreements or differences that arose during the process. Feedback from experts is an important step in understanding any differences in judgment

- It is important to provide transparent and clear interpretations alongside the final results after aggregation

Extra requirements for expert elicitation can be found in the appendix of the ZIN guidelines (in Dutch).

Looking ahead

The 2024 Dutch guidelines are clear on what is and what is not allowed with regards to expert elicitation. If performed correctly, expert elicitation may be an acceptable source of information for Dutch health technology appraisals. With adequate preparation and having the right expertise, it should be feasible to perform SEE and get a health technology appraisal accepted.

The Dutch guidelines are ahead of those of other European countries, who may also adopt new guidelines on expert elicitation in the future. Lumanity can help to develop a strategy for both Dutch and international questions about cases where expert elicitation seems to be the only option to gather information.

Contact us

Want to find out more about ZIN’s updated HTA guidelines in the Netherlands? Need assistance with conducting SEE? Contact us

References

- Zorginstituut Nederland (ZIN). Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg (versie 2024). 2024. Available at: https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/over-ons/publicaties/publicatie/2024/01/16/richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg. Accessed: January 30, 2024.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE health technology evaluations: the manual. 2022. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/chapter/introduction-to-health-technology-evaluation. Accessed: January 26, 2024.

- Horscroft J, Lee D, Jankovic D, et al. Structured expert elicitation for healthcare decision making: A practical guide. 2022. Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/che/research/teehta/elicitation/steer/. Accessed: January 26, 2024.

- Zorginstituut Nederland (ZIN). Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg (versie 2016). 2016. Available at: https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/over-ons/publicaties/publicatie/2016/02/29/richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg. Accessed: January 30, 2024.

- Kellerborg K, Perry-Duxbury M, de Vries L and van Baal P. Practical Guidance for Including Future Costs in Economic Evaluations in The Netherlands: Introducing and Applying PAID 3.0. Value Health. 2020; 23(11):1453-61.

- Kreimeier S, Åström M, Burström K, et al. EQ-5D-Y-5L: developing a revised EQ-5D-Y with increased response categories. Qual Life Res. 2019; 28(7):1951-61.

- RStudio. R Markdown. 2024. Available at: https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/. Accessed: January 30, 2024.

- University of Canberra. Evidence-Based Practice in Health. 2023. Available at: https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149721. Accessed: January 26, 2024.

- Hoffman T, Bennett S and Del Mar C. Evidence-Based Practice: Across the Health Professions, 2nd ed. Chatswood, New South Wales, Australia: Elsevier, 2013.

- Oakley J and O’Hagan A. SHELF: The Sheffield Elicitation Framework (version 4.0). 2019. Available at: https://shelf.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/home. Accessed: January 26, 2024.

- Dalkey N and Helmer O. An Experimental Application of the Delphi Method to the Use of Experts. Manag Sci. 1963; 9(3):458-67.

- Cooke R, Mendel M and Thijs W. Calibration and information in expert resolution; a classical approach. Automatica. 1988; 24(1):87-93.

- Bojke L, Soares M, Claxton K, et al. Developing a reference protocol for structured expert elicitation in health-care decision-making: a mixed-methods study. Health Technol Assess. 2021; 25(37):1-124.